Reformed Christian Apparel | Blog

Not all truths are equally worth telling. Some deserve a megaphone, and some even deserve a spot on your chest. At Tellable Truths, our store is brimming with pithy and deep words situated on comfortable clothes, and our blog is littered with thoughtful prose on radical things like God, culture, and purpose.

Featured products

-

In the Final Analysis

Regular price From $21.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Boniface | Peak Winsome

Regular price From $21.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Warrior-Scholar Shirt | Thucydides Quote

Regular price From $25.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Alfred the Great | Don't Pay the Dane-Geld

Regular price From $25.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per

Westminster Shorter Shirts

-

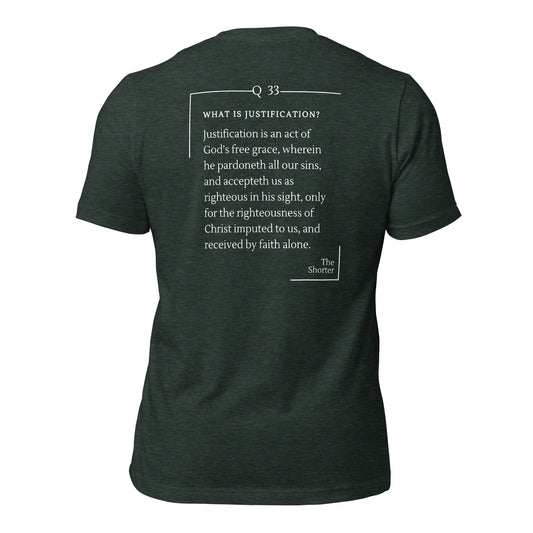

Justification by Faith Shirt | Westminster Shorter Q33

Regular price From $25.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Benefits of Effectual Calling Shirt | Westminster Shorter Q32

Regular price From $25.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Effectual Call Shirt | Westminster Shorter Q31

Regular price From $25.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

Union with Christ Shirt | Westminster Shorter Q30

Regular price From $25.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per

Worldview Collection

-

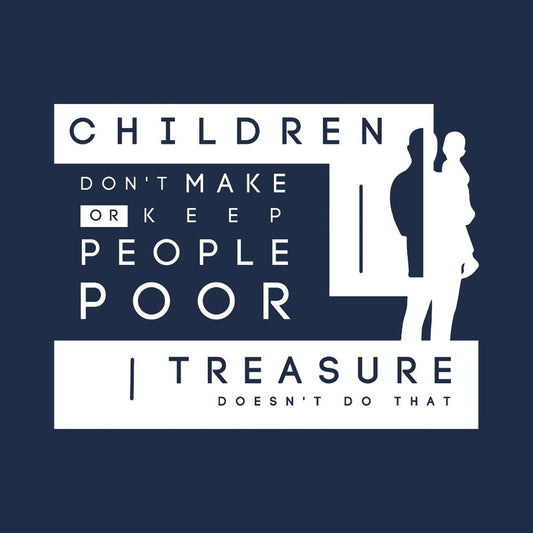

Children are Treasures | Worldview Collection

Regular price From $21.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

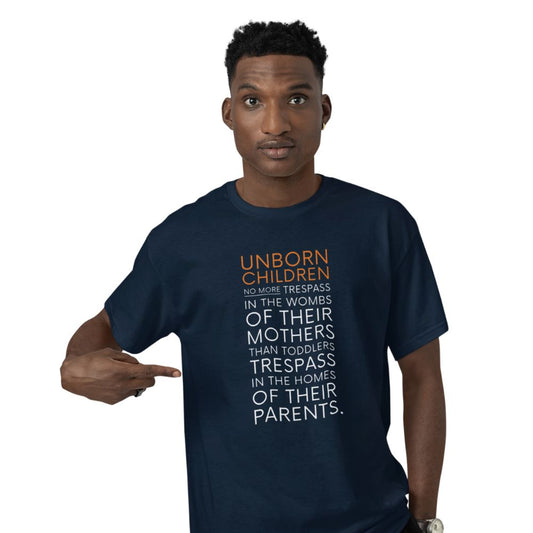

Unborn Children | Worldview Collection

Regular price From $18.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per$21.00 USDSale price From $18.00 USDSale -

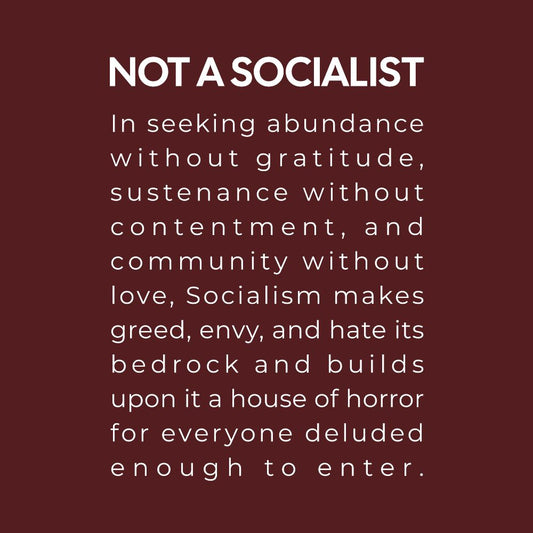

Not a Socialist | Worldview Collection

Regular price From $21.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per -

What is Death? | Worldview Collection

Regular price From $21.00 USDRegular priceUnit price / per

Hoodies for the Faithful

Boniface | Peak Winsome Hoodie

The Megaphone [Blog]

View all-

Reforming Utopia | A Christian Perspective on t...

Our history is a wasteland of sparkling and lofty dreams sabotaged by men in the mirror. But does it have to be that way? Is Utopia possible?

Reforming Utopia | A Christian Perspective on t...

Our history is a wasteland of sparkling and lofty dreams sabotaged by men in the mirror. But does it have to be that way? Is Utopia possible?

-

Why Does Anything Exist?

What could stand at the beginning and at the end, behind the veil of the present? Who is responsible for eternity in the mirror? And who can see it’s end?

Why Does Anything Exist?

What could stand at the beginning and at the end, behind the veil of the present? Who is responsible for eternity in the mirror? And who can see it’s end?

-

Natural Evil and God's Sovereignty

Pain is real. Babies are born still. Tsunamis don’t discriminate. Nightmares come alive. If God is in control, why does this happen?

Natural Evil and God's Sovereignty

Pain is real. Babies are born still. Tsunamis don’t discriminate. Nightmares come alive. If God is in control, why does this happen?

Alfred the Great Shirt

Embrace the indomitable spirit of Alfred the Great with this distinct t-shirt, a tribute to the Saxon king who masterfully balanced the sword and Scripture.